Last week a Facebook friend posed the question – what does the word warrior mean to you?

A combat vet friend emailed a couple days later to ask me for a definition of Warrior. I’m pretty sure some lovely woman asked him this question and he was struggling to get the answer right without scaring her with so much honesty that she ran for the woods. Nonetheless, it’s a valid and important question.

The Wounded Warrior Project is now treating us to extended commercials interspersed throughout our evenings of zoning out on the couch, staring at the television, and bemoaning the fact that there’s nothing of interest to watch. Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate the work The Wounded Warrior Project does. Though it angers me each time I see one of their commercials that an individual who goes to war at the biding our government, now has to resort to begging for donations in order to get top-notch care for the injuries sustained doing what he was ordered to do.

But that’s another blog post altogether.

My point here is that the word warrior is being bandied about with great frequency and it would behoove us to think about just what the term means to us.

I suspect, like most complicated concepts, the meaning is different from individual to individual. Therefore, I’m going to tell you my understanding of the word and I am asking you to comment and share what the word warrior means to you personally.

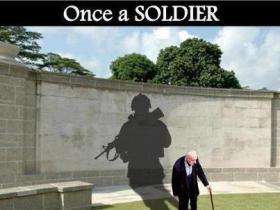

For me, a warrior is someone who has found a way, reached within themselves and found a power most of us don’t even know exists, to walk through horror and come out the other side alive. I, personally, never use the word warrior for anyone but a combat veteran. But I do not call them warriors because of what they did during war. I call them warriors because of what they do every single day since returning from war. Many have done things, seen things, experienced things that changed them. Forever.

No one goes to war and comes back the same person. No one.

The rules of war are not the rules of polite society. Battle is about keeping yourself and your buddies alive. Period. War traumatizes because what is required in combat is directly and dramatically opposed to everything we are taught, and everything we know innately within ourselves about the sanctity of life. Why else demonize the enemy? Why else work so hard to convince ourselves that for those we kill in war life and death hold different meanings than they do for us.

All of this denial of long-held beliefs in order to survive is burned into those who go to war. If it were not, none would return to us.

The courage, the incredible power of the warrior, is that once he returns to us, day-by-day, night-by-night he lives through the adjustment necessary to live among a society that does its best to transform his experience into flag waving honor when the warrior knows damn good and well there is nothing glorious about war. Nothing whatsoever.

Books by Pamela Foster

All books can be ordered through any bookstore or library. In addition they are available through Amazon.com as both conventional books and as download to Kindle

Redneck Goddess, Contemporary southern novel

Noisy Creek, Contemporary southern novel

Bigfoot Blues, Contemporary novel set in the Pacific Northwest

My Life with a Wounded Warrior, Personal essays

Clueless Gringos in Paradise, Humorous travel Memoir

Ridgeline, Historical Fiction, Western

The Perfect Victim, Suspense

Boogie with Chesty, an essay about a PTSD Service Dog